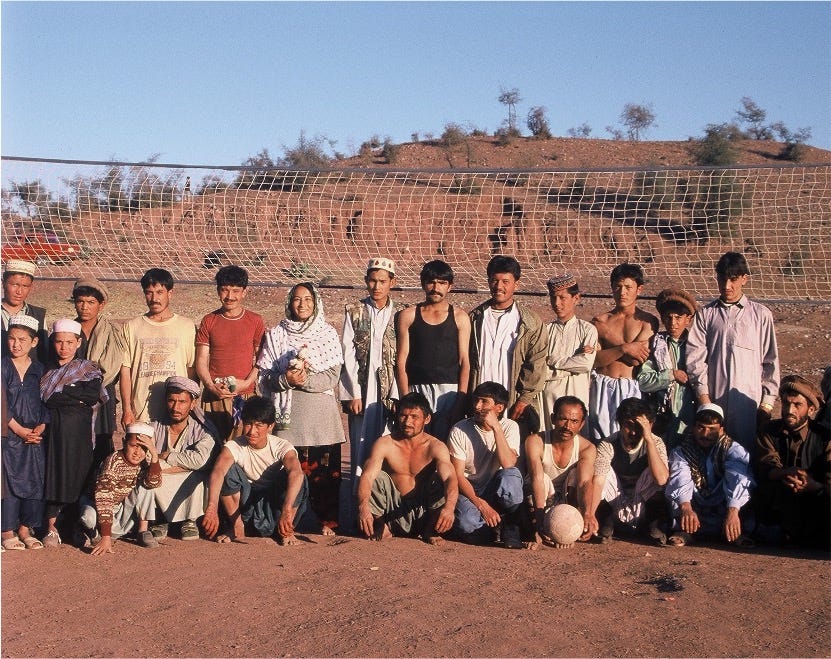

The sacred boundaries that I gazed upon in December 2001 outside Peshawar, Pakistan, wondering if I could cross to play volleyball with refugees from Afghanistan.

In December 2001, as bombs dropped in Afghanistan, I stepped over more than a line in the dirt to join a game of volleyball that boys were playing in a refugee camp outside the city of Peshawar in northern Pakistan.

A Muslim journalist born in India and raised in the state of West Virginia in the United States, I had been raised with a feminist interpretation of Islam that allowed me to spread my wings in this world. That day, I stepped across hudood, or sacred boundaries, that most often control the lives of women and girls, one Afghan girl that day watching from the sidelines, the boys not allowing her to join them.

That moment marked a new era that would span the next twenty years in Afghanistan for not just the country but women and girls in the country, as Taliban leaders fled in exile to the nation of Qatar, taking with them the most puritanical interpretations of our faith. New rights, new freedoms arrived. They came with the brutal cost of war.

But it was also, most ironically, a time of light, when girls and women could go to school without fear and feel the sun on their faces and the wind in their hair without punishment from the Taliban. They could play volleyball, ride a skateboard, laugh aloud and sing.

Twenty years later, we are in a new age.

In August 2021, the Taliban came back to power. They set about erasing women — literally, covering the images of women on shop fronts with white paint in a literal white washing of a new reality that set about to engage in a “cleansing” of half of the nation’s population from the public eye, as documented by journalist Lotfullah Najafizada @LNajafizada.

Suhail Shaheen, the Taliban’s deputy ambassador to Pakistan in 2001, was a man whom I had interviewed in October 2001 in the capital of Islamabad at his home with his two wives. He returned to Kabul as the new Taliban regimen’s communication chief and he is now the Taliban’s envoy to the United Nations.

Sirajuddin Haqqani, most wanted by the FBI for terrorism, is now Afghanistan’s new interior minister.

The girl who had to watch the game on the sidelines is now a woman, and Afghanistan is now a nation of darkness for women and girls.

Women’s heads were even beheaded from mannequins.

There is no cultural relativism to consider when we think about this simple fact: it is now a crime for a woman and girl in Afghanistan to feel the wind in her hair.

This week, in the city of Thessaloniki, Greece, a new exhibition, “Art Communicating Conflict Resolution,” was launched through an organization, Conflict and Art, founded by curator Vasia Deliyianni. There, beautiful embroidered dresses from Afghanistan hang as symbols of the freedoms in which Afghan women and girls lived for two decades. Around a wall are the suffocating blue burkas that the Taliban demand women wear today in one form or another, whether as swaths of black covering or heavy shawls, to cloak themselves and become invisible.

We must ponder: Can the wind in our hair be a crime? Or is it a divine right?

Through art, Afghan women and girls — and the men who support them — are crossing these man-made “sacred boundaries,” along with and they are expressing a resistance to the tyranny of thought that seeks to make freedom of movement, body and spirit a crime.

Here is a window into some of these artists and creators and what they are doing. Please send me the names of others you recommend adding to this virtual gallery with links to their work. And please support these artists and creators.

Rada Akbar @RadaAkbar IG

Rada Akbar’s photo exhibition “Invisible Captivity” was on display from May 5 until May 28 at Espace des Femmes @espacedesfemmesaf in Paris. The curator was @aline.pujo.

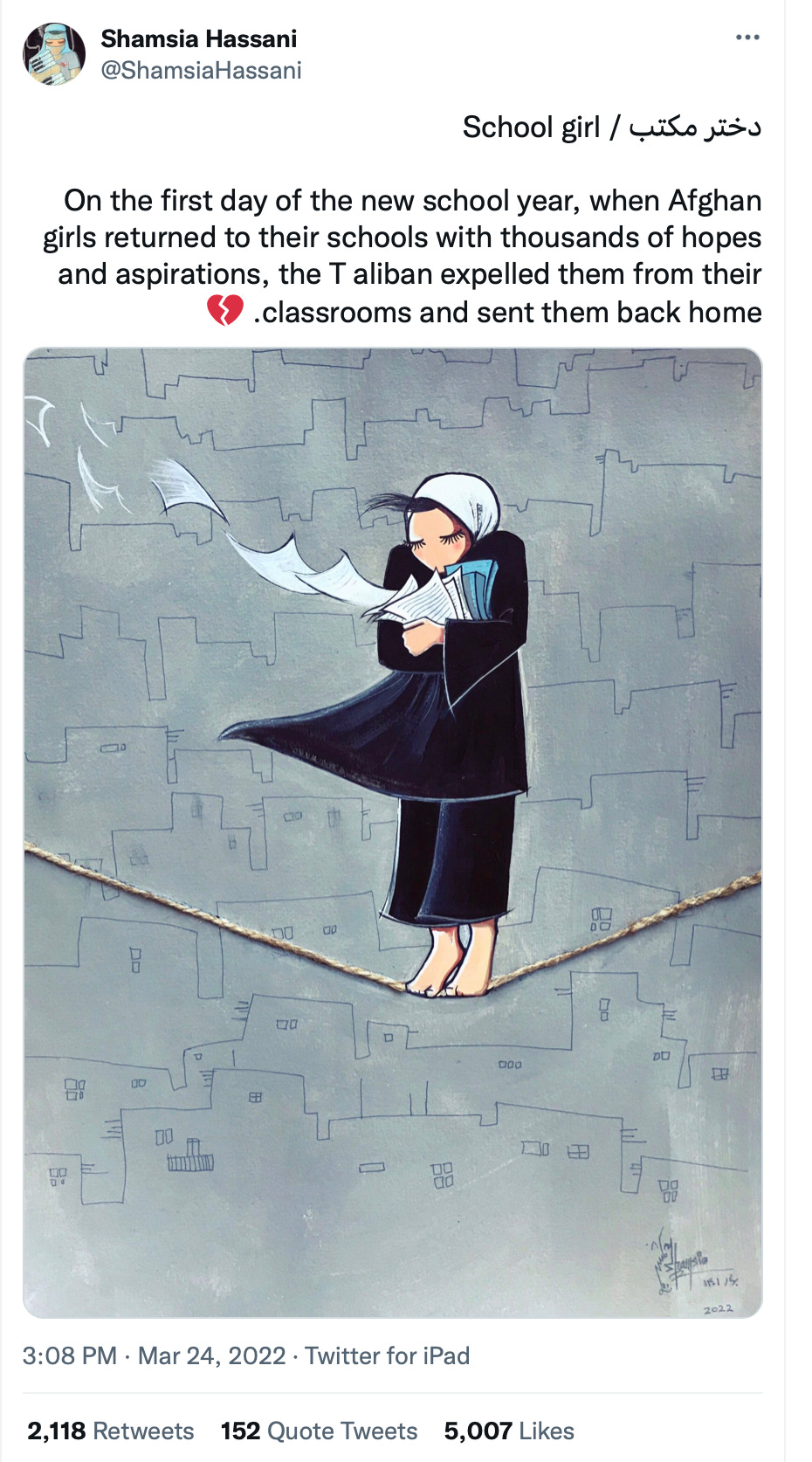

Shamsia Hassani @ShamsiaHassani Twitter— Graffiti artist

Shamsia Hassani is a young woman who became known as Afghan’s first graffiti and street artist. Her art continues in exile.

She painted imaginary graffiti on the cliffs of Bamiyan, where the Taliban destroyed huge Buddhist statues from the fifth century in 2001. The picture is part of her Dreaming Graffiti series, in which she enlarges photographs of places she would like to put graffiti, then paints a mural on pictures of locations she can only dream about.

Fatimah Hossaini @HossainiFatimah Twitter

Fatimah Hossaini is an Afghan photographer who has published a photo book, “Beauty Amid War,” capturing ironic images from Afghanistan.

Olya Morady @Olya_Mrd Twitter — Visual artist

Olya Morady is an Afghan artist and activist. Malala Yousafzai’s father Ziauddin Yousafzai @ZiauddinY shares her powerful voice on “Day 284 of Taliban’s ban,” where she speaks with the wind in her hair — in Stockholm.

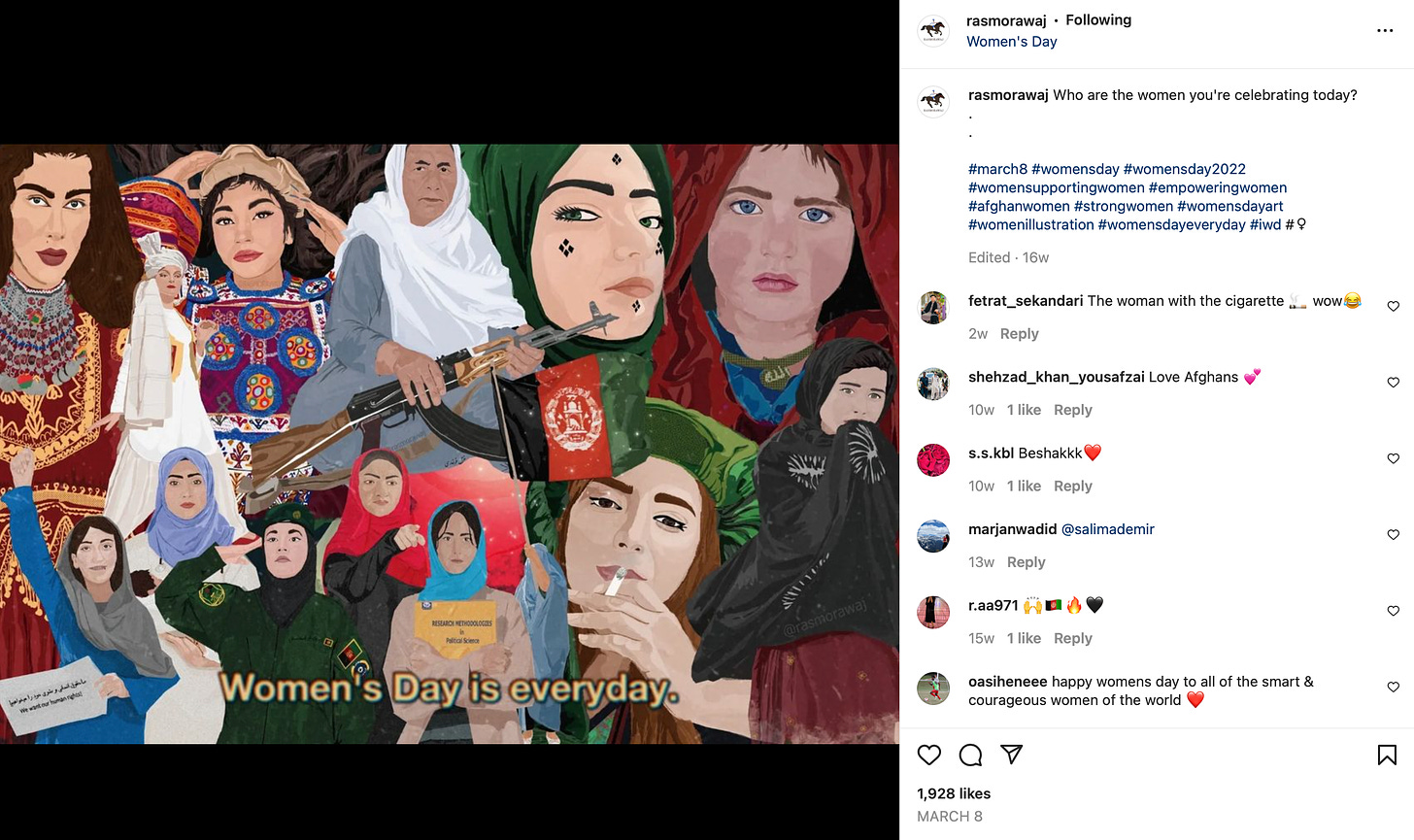

Rasmorawaj

Products inspired by Afghan artists for sale: https://rasmorawaj.com

Allies

Malala Yousufzai @Malala Twitter IG

You can see here protest art shared by Nobel Prize winner Malala Yousufzai. The art is used to advocate for the simple idea to #LetAfghan GirlsLearn. Growing up in Pakistan and shot in the face by the Taliban, Malala is an advocate for Afghan women’s and girls’ rights.

Masih Alinejad @AlinejadMasih Twitter

Masih is an Iranian-American journalist who has used her platform to launch an initiative, #MyStealthyFreedom, which advocates for the right of women and girls in Iran — and around the world, including Afghanistan — to live with the wind in their hair.